Conversations with the Dean

Featuring Professor Chris Abani

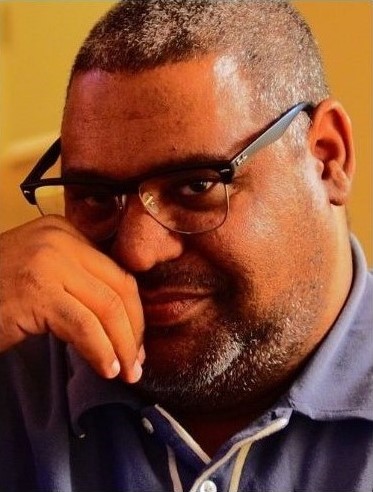

Professor of English Chris Abani and Dean Adrian Randolph discuss “ubuntu,” a concept that recognizes our interconnectedness, the importance of an English major in today’s world, and the Program in African Studies, which holds the largest collection of African and Africana books and artifacts outside of Africa.

Chris Abani is a novelist, poet, essayist, screenwriter and playwright. He is the Board of Trustees Professor of English and Director of the Program of African Studies at Northwestern University. Through his TED Talks, public speaking and essays Abani is known as an international voice on humanitarianism, art, ethics, and our shared political responsibility. His many research interests include African Poetics, World Literature, 20th Century Anglophone Literature, African Presences in Medieval and Renaissance Culture, The Living Architecture of Cities, West African Music, Postcolonial and Transnational Theory, Robotics and Consciousness, Yoruba and Igbo Philosophy and Religion. |

|

Adrian Randolph is dean of the Judd A. and Marjorie Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and Henry Wade Rogers Professor of the Humanities. Dean Randolph's research focuses on the art and architecture of the medieval Renaissance Italy. He joined Northwestern in 2015 from Dartmouth College. There, he served as the associate dean of the faculty for the Arts and Humanities, chair of the Department of Art History, and director of the college’s Leslie Center for the Humanities. |

Watch more "Conversations with the Dean"

Conversation Transcript

Adrian Randolph: Today we are really lucky to be joined by Chris Abani. Chris is a novelist, poet, an essayist, a screenwriter, and a play writer. He is the Board of Trustees, Professor of English, and the Director of the Program of African Studies at Northwestern University. Through his TED Talks, public speaking and essays, Abani is known as an international voice on humanitarianism, art, ethics, and our shared political responsibility. His many research interests include African Poetics, World Literature, 20th Century Anglophone Literature, African Presences in Medieval and Renaissance Culture, The Living Architecture of Cities, West African Music, Postcolonial and Transnational Theory, Robotics and Consciousness, Yoruba and Igbo Philosophy and Religion. And I could not be happier to have my colleague and friend, Chris Abani with us today.

Chris Abani: Hi, good morning. Thank you, Adrian. That's a bit ticking, that's a mouthful. I was like, wow, who's he talking about?

Randolph: Yeah, you've done a lot. So first question, years ago, I don’t know exactly when, you gave a Ted talk where you emphasized the concept Ubuntu, the Bantu term. A concept that recognizes our interconnectedness.To be truly human, we must reflect on each other's human, or each other's humanity back to one another and some sort of mutual vortex or circuit.

Abani: Correct.

Randolph: We discuss this concept with students in today's world, and perhaps this year in particular when understanding our shared humanity has never been more essential.

Abani: Right. I do, Ubuntu is, is a, I mean, it's the most recognized by that term, but I think it's a very common human experience. And the idea is quite simple, that the only way to be human is to have a reflection of what that means. So it sort of includes the ideas of what a social contract is. But it sort of negates, I think in today's world, this dependence on a kind of hyper individuality. So in Igbo or what's, Bantu is a sort of a term that covers, I think everyone from Zulu nations all the way through the Congo to Igbo nations. But the concept is more of a communal individual. And so the idea is that your eccentricities are encouraged and allowed in so much as they do not threaten the general fabric of what is good communally. And the, you defer to the community in so much as the community is not attempting to erase all of your quirks. So the idea is it's a constant negotiation back and forth. And I really love this idea. And if we didn't get all the way down simply to language, for a while when I was younger, I spent some time as a, as a guest of the Nigerian government in a situation where I was not speaking to people. And after six months of solitary, even the way I talked shifted, and I sounded more the way a person with hearing difficulties might sound because there's no, in other words, even the cadence of the words got, so I had to relearn how to talk because even at that basic level, there is no reflection back at you. And so it's hard to calculate, to gauge, you know, it's a bit like a very common and completely different example would be if you have really loud headphones on a train and you might not realize you're shouting when you think you're talking. And so that then means that you're dependent, in other words, the thing we think of as consciousness or even parts of it, like conscience, is dependent on a kinda mutual negotiation. And so community is vital in the sense that community doesn't mean the people who agree with you. Community is the people you've made a commitment to work through difficulty with. And so that's, that kind of friction is really what shapes what is human, because it always involves risk. And if there's no risk, then we don't really know how to measure anything.

Randolph: So you very gracefully introduced a key moment in your biography or autobiography, which I'm not sure everyone would've caught because you put it in such a creative way. And I don't, you don't have to dwell on it, but when you say you were a guest of the Nigerian government, you were referring to being imprisoned. Is that correct or did I misunderstand?

Abani: No, you understood. I just like, you know, I was very young and I'm, it was my eight, I was 18 to in my twenties. Let's go with that, and it's 30 years ago now. So I try not to sort of bring it up in such a direct way because so much of life has happened and has tempered me in so many different ways. But it was really, I thought it was a crucial way to really talk about what I mean by how we're using this term Ubuntu really as a, the reflection is a gauge, right? Especially in, as you pointed out, the difficult times we're in, not just with the moments we're all negotiating around sort of what's happening in the Middle and near East, but also just in American politics, how we've shifted, it seems, from disagreeing on principles to a disdain almost for people who don't share the same principles. And I think that that, that is the collapse of Ubuntu.

Randolph: Yeah, and I am, I assume your written works, spoken works, and interventions in the creative sphere are enacting this form of commonality in some way, opening up lines of communication with other people. And I'm going sort of off what I said I was gonna ask about, but I'm curious if in your writing or creative practice you find that, you know, sort of what, you know, Bakhtin called about heteroglossia or something. You know, there's sort of multiple languages flowing through you. Do you find conversations like this or do you find working with other people, either formally or informally, is part of how you generate community through your own writing practice?

Abani: I think so. I think the part of the beauty of having a creative practice is that it's, it's sort of one part of a lived life. That's why I often don't refer to myself as a writer 'cause it's just one role, right? You're also a teacher, you're a father, you're all different things. But I think that the beauty of that is that you can distill that interaction. And so usually in my creative work, I am interested in recuperating erasure. So, I always sort of, another Nigerian writer described my work as choral aesthetics, chora in Yoruba means the alleyway. So sort of the space between clear buildings. And so it's sort of looking at people or circumstances that really threaten cognitive dissonance. And so how we erase these difficulties and I'm trying to recoup them, but not recoup them through spectacle, but rather almost as another way of extending the spectrum of what we think of as human.

Randolph: So I'm going to zag a little bit because as I mentioned in the introduction, you are both a teacher and a professor in the department of English and the Litowitz Graduate Program. But you're also the Director of the Program in African Studies, which I didn't tell you, but for the audience, is the oldest recognized formal program of African Studies in the United States, and also a hub of interdisciplinary collaborations in areas such as medicine, law, library, the art and journalism. Could you share some insights on how interdisciplinary research enhances our understanding of complex social issues? And perhaps directly relating it to, and this is a big question, but you know, some of the changes that are happening in Africa, I mean, you know, it's obviously a huge space and I don't want you to feel you have to comment on everything, but there are certain patterns and things going on.

Abani: Right. Yeah, I was even going to say in the term English, when you think of English, Department of English, it used to mean a particular thing, but I think even in Northwestern in the English Department, we thought about maybe a name change because everyone who teaches in English also is, has affiliations in comp lit, in gender studies, different clusters, Middle East and North Africa. So the idea of a classical English education is so different in a, in this modern context and makes English one of the most vital departments in a college of humanities because it straddles, it is itself a a kind of hub and the faculty are working across these areas. But I think traditionally, African studies has always sort of, I would say for the, for a long part, it sort of evolved with a kind of west looking into study Africa, which has kind of created a one-way relationship to material. And even as an art historian, you know, some of the people who go and interview people talk about native informants rather than the idea that this is someone who's a colleague, he might be, he's sort of a professor in a non-academic setting who has, is an expert knowledge, sharing expert knowledge. And so I think what's happened is that African studies has moved away from that model as you start to see across all of the humanities and sort of become more of a conversation between what you might think of indigenous knowledge producers. And that can be anywhere with, from sort of the ways in which Derrida is read in Africa or Shakespeare's read in Africa to particular practices and systems that are completely indigenous to the continent, but also dealing with certain things like, so as we move into 2025, we are looking at mega cities across the world, and more, half of them are in Africa, Kinshasa, Cairo, Lagos, and bits of like Johannesburg populations bigger than countries. And then now you start to have this overlay of technology happening where in Egypt, much of the infrastructure shifted out of Cairo and then satellite intelligence cities are being built, and all sort of this, this whole idea that's come out of some of the collaborative work with the humanities and architecture with companies like Nokia way back when. So on the continent, things are moving so rapidly and the stock exchange, for instance, in Lagos and the stock exchange in, that you find in Ethiopia has had an equal impact on the global economics as any stock exchange in New York. So it seems like a lot of the other, what we think it was business or money geared interventions, their expertise and knowledge and medicine as well is moving much faster than, it's almost like the humanities are chugging along behind because it's a different practice. One is sort of an immediate kind of production system, and the other one is sort of evaluates the more human relationships within that. And that takes longer, but the shift is happening. So I think we're shifting more to a collaborative model. And then when you come to interdisciplinary, it's really a fascinating word, everybody loves it, everybody wants it to happen, but we still sort of, you know, when I used to work in, in the social housing in the UK, we came up with this idea of cost sector management and you, everybody sort of trying to protect their budget and make sure that their cost centers as important as, and interdisciplinary work requires at even at the higher administration level, a kind of shift in the evaluation of projects. And so it's sort of like not seen as you are deviating from your core programming to do something else, but rather that this thing is part of the core programming. So I think what's happening over time is that we are trying to figure out what that can mean. But I think it, part of the most difficult thing I found in interdisciplinary research and work is the fear of failure. So that we sort of live in a time where the pressure to be productive, to be successful is expected to be immediate. And so it makes experts hesitant to sort of work with other experts and they're like, well, I don't really understand how we're measuring this. And you're like, neither do I. But I think the cumulative failure sort of opens up a wider question, and it's sort of almost like, you know, as rabbi, as a rabbinical tradition is not to find the answer, but to find a better question. So I think of interdisciplinary as not the idea that the project yields a definitive answer, but that it actually yields wider questions. Exactly, which continue to grow in multiple ways.

Randolph: I loved what you said, going back to what you earlier said, I just happened to hear a podcast about a new book by Zeinab Badawi, An African History of Africa. Which is premised exactly on this notion of there's been so many histories of Africa from the outside and there's many histories of Africa from Africans, but they're less visible. In the, let's say non-African world. And so it's really great to see that sort of circuitry being remade in a way that we can hear multiple places. And you are right about interdisciplinarity. It, the word disciplinarity is very challenging. And as you said, in the same time as you were talking about English at the beginning breaking down, because of course English itself is a anglophone world has transformed into so many different dialogues of English. English is a global language in ways the disciplinary nature of English has changed as a unit. And that's happened in many, many departments. And at the same time, we're talking about interdisciplinarity, but we don't no longer have those disciplinary assumptions we used to have. So it's a very fluid moment in the academy about knowing where things should happen or how they should happen, which is a great opportunity. But I couldn't agree with you more that there's a, a pressure to, let's just say measure in some way. I mean, or account for things, and without those disciplinary boundaries, it does become complex, you're absolutely right. But I think the Program in African Studies is a great example of something that seems to work really well. I mean its had a storied past here and I think partially because of the strengths in english and history, it's done and in political science, I think it's really a very interesting area. It does mean that a lot of the humanistic work is put in direct connection to a lot of the history and politics of Africa in a way that I think has been very fruitful.

Abani: Extremely, and we've had this, I mean, through your own office, we've had a hire of a very vital faculty member with Akin Ogundiran who's not only just looking at history, but the material history of Africa and sort of creates centers both there and here. So that is being studied, but you know, all the things that are happening really Akin, myself, and people in anthropology are, are moving into AI and looking at the ways in which that material history can be preserved and studied in virtual contexts. We have a graduate student, Craig, who did this amazing work that you can literally, the idea is almost like you can curate an exhibition where people can physically, physically, virtual, virtual, it feels more physical, but it's like you see those videos of people with VR spectacles crashing into walls and stuff. It feels that way. Interacts, so I think that that's also what's beautiful about inter, and where African studies sort of has been excelling because it's already a syncretic culture, right? The notion of Africa, the term itself is already a synchronization. And so it's sort of this moment that allows us to be, we are much more, I suppose, responsive and fluid in that way. So that's been vital to our success as a field of study, is that we are part of every field of study.

Randolph: I'd say, I went to see Craig's work in the library, and it was amazing. For those of you who are on the call, you put on these VR spectacles, and you walk around and you can see summoned up almost in a quasi-mystical way, either completed objects or objects that aren't there, but are holographically somehow brought into existence and you can manipulate them and be there. It's really, it was quite extraordinary. And I think it is true that in some of the areas, and in fact that touches on a point I wanted to get to. I was just reading through, you know, it's not going to be reversed, but one of Chris's recent publications, and in your introduction you refer to what I think is a major issue for the interface of a literary discipline and African cultures broadly writ in that so much of what constitutes African culture is not necessarily recorded in the same fashion as, you know, the literary canons of let's say, the European tradition. And you talked about Akin's work in archeology. There's other people who work on fabrics, other people who work on ceremonies, rituals. And so how do you reach back to understand the complex legacies where the written word isn't necessarily the prime documentary fact that reveals something? I don’t if you have a comment on that, but there's something about being in an English department that's interesting in that regard.

Abani: Well, yeah, but it's also what is, what is also interesting is that there is, we have huge swats of timba in Timbuktu in written manuscripts. But even more interesting, you have written in Ge'ez, which is the liturgical language of Ethiopia, the Ethiopian church, you have geographies of saints which go back to The Middle Ages, and reference Europe. And you know, Wendy Belcher at, appear at, Princeton, who works closely with us in certain projects, has done a whole beautiful study about even the how medieval Christianity is affected by African Christianity. So there is a, there is a written record, but there's also, but it also is very modern thinking when you think about someone like, you know, philosophers like Derrida, who, to whom the text is not just what's written down. A performance is a text, a scene at a restaurant is a text. And you begin to understand that, that the, the way of reading is different, but also you realize how much influenced by Christianity and this idea of an original God affects intellectual thought. So the idea, Darwin doesn't invent the theory of revolution, he just published first, we know there were people around him who were, so this idea of attribute into prime causation, singularity is something that's very absent from African thinking where knowledge is passed on collectively and you, people add, even in a performance, people are modifying the performance and don't necessarily gain credit. So jazz would be an American medium that does that where sort of the person who is a session man on a jazz recording is as important as a man whose name is on the album, and within jazz musicians in that person's, like Coltrane's performance song Kind Of Blue, which is a Miles Davis album, kind of eclipses Miles Davis for the musicians, but for the, so it's sort of, it's really beginning to ask ourselves. And I think you see this happening with younger people. The concept, and you see this sometimes in not so positive race, which kind of forms of, you know, plagiarization is a very heavy term, but non attribution, the idea that knowledge exists out there, and if I found it, I have access to it and can use it and make it mine is actually not a new concept, it's such an old concept. And so the academy is struggling I think constantly, especially with the introduction of AI, about how do we measure that? Not so much in punitive ways but in generative ways. In other words, what is a new way of thinking about text and generation of ideas and material, not just about soul attribution, but about a collective process and comes back to interdisciplinariness because that is the lack of being able to attribute credit makes interdisciplinary work very hard because then people are devoting a lot of time for which it's hard for them to go to a promotions board and be like, well there's also this thing I did. And they're like, well you didn't do it, six of you did it. And so it's sort of like, I think that you're right, we're in a very fluid time where how knowledge is measured and where it can be measured has shifted a lot. Both in terms of technology, but a kind of return to what other cultures have often embraced.

Randolph: And I love, I mean the sense that weaves back to Ubuntu, right? I mean of the production. So shifting the very terms we use to conceive of knowledge might be a way of getting away from the idea of an autonomous knowledge producer towards something else. I did want to refer, I don’t know if anyone, I was in New York and saw the exhibition at the Met, the African and Byzantium, which for me, embodied precisely what you were saying, 'cause I saw objects there that I had no idea existed in Ethiopia from sixth, seventh century of, you know, sort of European time. But it was fascinating to see. So we've already touched on this issue, but I had a question about the value of the humanities in today's world. And I, you know, obviously you and I are both humanists and we care by virtue of how we're spending our lives about these things. But I wonder what you say in conversations you must in either your family or broader community face skeptics. And I'm just curious, you know, if there's any way you respond to people who might query, you know, why should a student pursue, for example, a degree in English?

Abani: Well, purely because a degree in English isn't just English, right? So first of all, you know, you could be, if you were, say you had a background in a Spanish speaking culture now and you were first generation, by doing English, you're actually, you could be blending into Latinx. You could be looking at sort of things that are very specific to a language which exists outside of English, but which is being studied within the context of English. So then your degree becomes not only relevant in terms of a modern system of study, but becomes a recuperation of a lost past, becomes a way of integrating families into a larger fabric. So there's all of that sort of level. But I think, you know, it always boils down to this, for me, medicine is amazing. Like we wouldn't be talking if we didn't have penicillin, most of us wouldn't be dead, or just a level of pain that 19th century person would live in that Tylenol just takes care of. But it's sort of interesting when we arrive at a culture through archeology or through history, we don't really concern ourselves so much with the technology of the culture. We concern ourselves with the fabric of what makes them human. So even as we talk now with medicine in the West, it's not so much just that we have an MRI machine, but the impulse to produce an MRI machine does require a certain kind of technicality, but it really is a deeply human impulse to serve, to open up, to preserve life, which, the study of which will be more in the humanist level with an ethical level. And so you see schools of medicine, for instance, taking courses in creative writing, asking questions through novels about ethical situations, because I think that's what education probably was prior to the enlightenment. I think that enlightenment sort of fragments things into specialized areas. But I mean, when you think about it, most of the education was, in fact, someone has argued that the bubonic plague had created the dark ages in the sense that the most educated person, and created so much problems in the church because the most educated person used to be the priest. He spoke Latin and Greek and could read and could write, but then they were serve, they was on the front lines of the plague given lost rights. And so we're dying, and so the length of time it took to study to become educated, to be a priest, there was no longer time. People were like, you are alive, you have all your teeth, you're breathing, come inside the order. So I guess what, the argument really is that anything worthwhile about being human is held and studied and examined in the humanities kinda realm of things because, precisely because it's absent of the kind of pressure that a medical doctor faces in a heart surgery situation. It's sort of, it has time and some of this stuff, Ubuntu takes time, it takes a measure. We have to be able to make critical mistakes in knowledge in order to reformat even the question we are asking, which you can't do if there's a million, a billion dollars of stock market that's taking a hedge fund. So in a way, I think that the value of it is that we bring a sort of solid and compassionate knowledge that sustains momentary breakthroughs in time, but creates a steady aperture of culture. I think that's why we're vital. And I think again, it's foolish of anyone to think we're not, because the idea that economic theory doesn't exist is not sort of linked directly to sort of class, or in fact even the idea of history, you know, the 20th century in many ways, both of us having backgrounds in England is a Scottish century. Almost every advancement made, both in terms of philosophy and technologies comes out of Scotland, which is a deeply humanist culture, has been for centuries. In fact, that's been the big divide between, you know, the Windsor and you know, so it's sort of like, it's a, it's not just vital in a philosophical way. Anybody with an English degree could work at the UN. They could work in a merchant bank, they could work in a hedge fund, they could work in advertising, they can write a novel, they can make a mean coffee in Starbucks, we're training people who are competent, and I think that's really what we want. We want a level of general competency. That is what sustains everything rather than an individual brilliance is.

Randolph: I wanted to remind the audience that in a few minutes, we can go to a more, well we're already an informal Q&A actually, so that's great. But if you have questions out there in the cyber world, please put them into the Q&A. I'm glad we'll try to field them. Chris, you just mentioned a couple of things that really interested me. One was the temporality of the humanities, and I don't want to sound too jargony, but there's something about the long sense of knowledge versus a type of instrumental knowledge which is immediately solving a problem. And I really, I don't know, that mapped onto some of the things I think about the humanities as well, that we are participating in a river that is quite long and broad as opposed to a rushing stream that is going very, very quickly. And the second thing was about mistakes. And maybe we can come back to that 'cause we chatted just a bit before about mistakes and the importance of, you mentioned it before, failure, mistakes, misperceptions, errors are a key part of creativity. So first of all, in the temporality, which I, and maybe I'll link it to the question I have here about your teaching experience, 'cause of course we're on the quarter system, which is probably one of the more rapid teaching sort of ways of delivering education in this country. And I'm curious what you think about the time maybe in the classroom and in your own scholarship.

Abani: Right, so I mean, when you think about it, a theoretical physicist like Einstein or Michio Kaku, they have a lot more in common with a humanist than with say, an engineer building a bridge, right? But also, there are moments when if you were to go over the golden gate at 5:30 AM just as the fog is lifting, what you see is not a bridge. You see a moment of poetry, you see something that deeply can affect your love of a whole geography and is achieved by someone who probably that was the least important thing to them. So that, this is what I mean by misunderstanding that it, the misunderstanding that impulse of making a bridge, not just being about the tension of the cables and all of that, but also about this moment when someone steps onto it and has a mystical breakthrough. So that's a misunderstanding of the concept of a bridge. But also like a bridge is also this notion of connectivity, which is, you know, just philosophically a bridge and a peer are two separate things. One is an abrupt betrayal and the other one, the other one carries you through. So that even when you were, if you were to think about the idea of if you were settling, if you were a diplomat and you had to work between two cultures, you are building a bridge and down to the level, if you think about a much technology was invented to build a bridge. So sort of the technology doesn't precede the creativity, the technology and the creativity are the same thing. And so it's the same thing you need for everything. So temporality is important about all of it, but also the idea that you are building things that are lasting that have value, that you are part of a, you put your part of a piece of knowledge into a larger piece of knowledge that becomes human. So that's the other part of it. But when you talk about teaching, so when I first, I started teaching actually in UC Riverside, which also works on quarter systems.

Randolph: Oh yeah.

Abani: And it was an, that is really where I learned how to teach the quarter system because first of all you don't realize how much privilege you carry. I think part English part Nigeria, but I arrived in it's like oh we have 10 weeks so here's 10 novels, it should be a novel a week. We'll be fine, it'll be great. And then sort of like come into the realization that I'm working with a population sometimes whom English is a third language that I'm working with multiple class systems where some people went to high schools where they never read a whole novel, they read parts of a novel to pass a test. So this high school is not closed down for funding reasons and really kind of realizing for the first time the assumptions you we make about the things we carry and having to learn after a while, you know, I was teaching and I called my brother in England and my brother didn't go to, he's the only one of us that didn't go to uni. So it was often seen as a black sheep and sort of complaining to him like, you know, the whole generation argument, this generation don't know anything. And so my brother said to me something that's so African, he said, you know, there's something, remember when granddad used to say that if 16 people tell you you smell, you should take a shower, then go and argue, 'cause then for sure you know, you don't smell. Like the only common denominator between all these failed teaching experiments is you. So maybe you need to think about how you are teaching and when you are sure you are doing a fantastic job, then come back and complain about the kids. Such a pivotal moment for me because I realized that I had to then rethink a whole pedagogy. How do you connect? What are you doing? I grew up text-based, they grew up more vision-based. I grew up sitting read, you know, I was, I read the, I remember reading a thousand-page novel as a kid and thinking nothing of it. They don't have that. So then what do you do with what you have? And then I started to realize the part of the problem was I would disregard what they knew and then attempt to give them something I thought was more valuable. And so the first shift was sort of to find out where they are, what they're listening to, what they're reading, what they like, and to bring the same sort of matrix of critique to those things, and establish value in what they already lived in. And then it was easy to say, well come over here from Harry Potter to, to read some Hemingway because then now they feel seen. And so it's really critical that you have 10 weeks because it really asks you what is the most important thing you have to communicate. And you realize after a while that it's not information. It is how to learn. You are teaching young people how to think with rigor critically and that you don't need all the time in the world and all the material, you need to figure out what it is about this particular amount of information you have to give. But teaches them so that each successive 10 weeks, that bringing the skills of thinking and integrating along with them so that there's less and less work to be done. And what that forces you I think as a researcher is to clarify the questions of your own research. Why is what you're doing? It's, no one should care just because you think it's nice or you think it's important, they should care because they can locate something of core value to themselves within the thing you're offering them. So I think that the quarter system is an invaluable way to hone teaching, hone research and provide an, and really amazing experience for young people.

Randolph: That's great. You know, I still, I've taught in the quarter system my whole career and I'm still vexed about it sometimes, but I think that was one of the better arguments for its, and I think it's got pros and cons, but I think you're right that it does force us to dispel this notion of just filling up a bucket. You can't, it doesn't really work. Just before we got on, and I'm going to go a little off to the side here 'cause I think it's relevant to what you just said. We were talking a little bit about translation and, you know, your work has been translated into many languages and you were talking about the desire by some people to have utter transparency and equivalence between let's say, the meaning or the words taken from one linguistic system to another versus the notion of embracing, let's say divergence and errors. And I think that has something to do also with students and I don't, can't quite put my finger on it, but I think there's that notion what you were just saying about meeting them where they are, but also valuing where there may be mistranslations or cultural mistakes that maybe become generative. So that's an open comment for you.

Abani: Well, I mean a good way, it is, it speaks even again to this idea that you know, of multidisciplinary learning. So I'm a self-taught musician, I'm self-taught saxophonist. And so you spend a lot of time if you're self-taught trying to learn from other people. And so I remember listening to this brilliant conversation, Braford Marsalis, who's probably one of the most interesting saxophonists alive today and musicians, he's talking about when he's young and he's sort of playing in Max Roach's band and Max Roach was a drummer. And then he gets up there and he's like doing all this crazy riffs and all of that. And so he says to Max, how was that? Max says, I'm gonna have to fire you if you can't change, 'cause I'm not looking for a saxophonist, I'm looking for a musician. And I think that, I think that we forget as academics that nobody's interested in an academic, they're interested in a conversation. And so what you think is the most important thing is a skill that is largely for you and for people in your particular discipline. But to be able to be accessible becomes vital in this way. And so for me, I remember I sort of, I did an event in the 92nd street, why New York with Elias Khoury is a Palestinian writer. At the time I had a book out called the Gate of the Sun, amazing historical work. And someone asked him this question, 'cause you know, there's always this thing where certain writers have very fraught relationships with their translators. And I was like, well no, every writer has a fraught relationship with a translator, 'cause it's either that the writer's been overly controlling and once, not even what I would think of as a translation, but a translation, which never works. Or they have people like me, who want them to retell a thing. I don't want a translation, I want to retell it. So if there are things I say, you know, Nigerian, one of the languages English is in Nigeria is what we call Pidgin. And it varies from region to region and a lot of it is punning. So in Warri, part of Nigeria, when they used to say, how are you, would be, which one? Means what's up? But then I'll notice people in the moment would sort of say, someone would say, ah, which one went to which. So people come be like, ah, which, and the other person would say, I'm fine I dey. But then another person would say, ah, wizard. And I was like, wait, what? And then I realized that he's punning on that word, which, which W-C, W-H-I-C-H has turned into which, and so wizard is punning on which, but he's saying, yeah, it's transformed, I'm having a great transform day. And so you'll find even within that particular culture that there are levels of access that are not even available to your average speaker, then if you pull out to a country of 200 million people that you pull out globally. So I think that misunderstanding becomes beautiful because I think that what happens is, first of all, it really cues you into, in a nonjudgmental way, to how another person is perceiving the same thing you are perceiving. Which then asks, makes you ask the question is, is this a completely different thing that is being transposed onto something or is just a facet of this thing that I have disregarded? And just that pause, it's a pause, because every thought kinda creates a pause to think about it, forces the conversation to go in a potentially different direction. So that, you know, I, years and years ago when I just, I had just left grad school at USC and I had an opportunity to spend a couple of weeks at the media lab in MIT. So I was only there for a couple of weeks and I chose to work on robotics and consciousness, because I was very, I'm very interested in the idea of irreverence and what, how does it, how can you make, how can you create organic irreverent code, right? Renegade code. Because it helps you understand how human beings think and how language works in these different ways. And then I remember getting very frustrated very quickly and feeling ashamed that my, that I wasn't seeming to go nowhere and that, but everyone in the lab was excited and I said, why are you excited? And they're like, oh, if you haven't failed 90% of the time we don't even know that you know what we're measuring. And that was just, it was really mind opening. The idea that if you walk into a Toni Morrison novel and you're only interested in a particular kind of feminism in that particular kind of Toni Morrison novel, you miss a whole universe. And so what you have to do is to sort of allow, you have to create a, what I call a basic competency so that you know, you can move on in the world, but you need to fail for yourself with your knowledge repeatedly in order for you to even expand the parameters, to begin to ask questions that are wider and more inclusive. And if you have to live in the fear of making mistakes, especially interpersonal mistakes, then how the hell can we be studying anything if we have to be, you know, that's, so we're in a very, very precarious time right now with this whole idea.

Randolph: I think that's a creative and wonderful way to draw to a close time. The clock tells me it's at the end of our 45 minutes together. Chris, it was fabulous hearing from you. I want to continue the conversation, and to all of you out there, thank you so much for listening and attending, and we look forward to the next Conversation with the Dean.

Abani: Thank you very much.